Created by

Kento Cady,

Fellow, Caring Cultures 2025

Published

February 6, 2026

Definitions

- Guilt

- The feeling of deserving blame

- Fear

- Anticipating danger

- Vulnerable

- Being able to be easily harmed, influenced, or attacked

- Open

- To be completely free from concealment : exposed to general view or knowledge

- Care

- Creating and nurturing conditions for everyone* to thrive

*Everyone: including the caregiver!!! - Reciprocity

- Mutual dependence, action, or influence. To be shared, felt, or shown by both sides.

Special thanks to:

Sania, Ashley, Maisie, Key, Zoe, Nasim, Setareh, Wren, Vincy, Tara & Biscotti

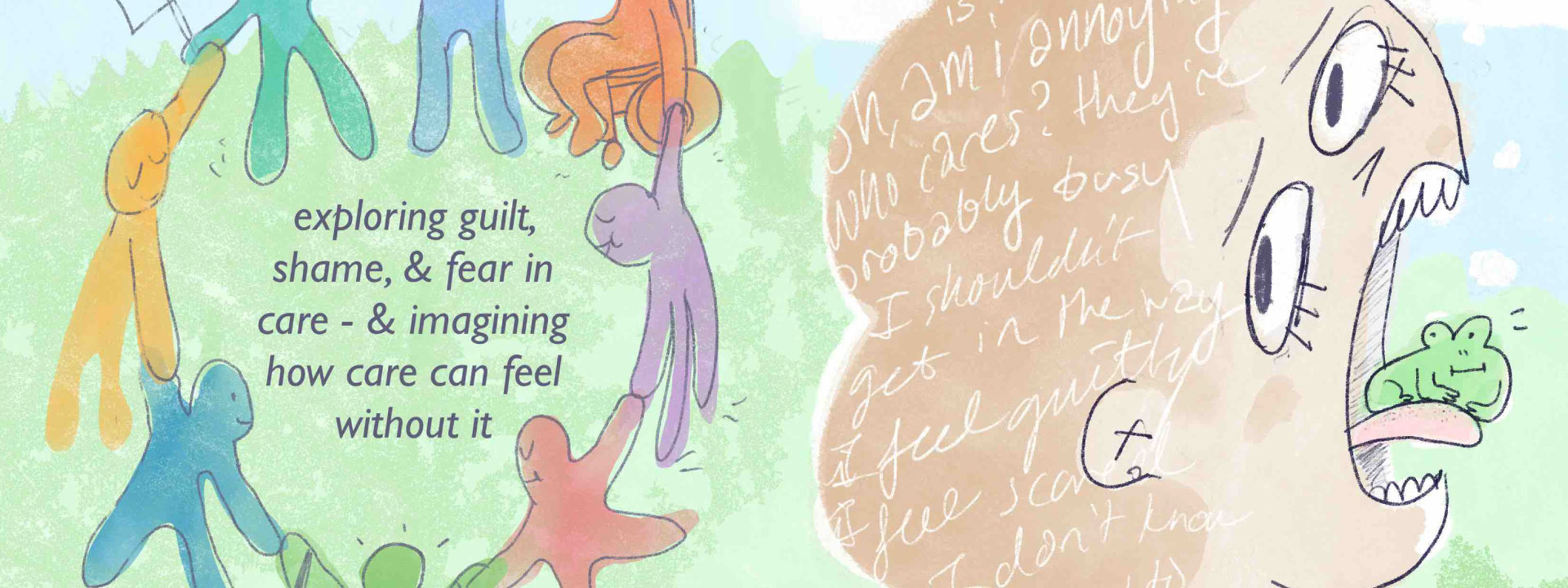

Why, guilt … ?

When I signed up for this fellowship, I thought that as a children’s art educator, I knew a thing or two about how care shapes futures. I’m surrounded by caregiving as a profession — and I see the burnout, the joy, and the instability of the job every day. I intended to examine care as labour, but on the first day, the most basic question threw me for a total loop:

“How can we help care for you?”

Now, day one, I was in the zoom meeting recovering from a terrible bout of norovirus, passed on to me by a partner. I was weak from fluid loss and vomiting all night. Bleary, shaking, and in bed, my first thought in response to the simple question was a defensive “I don’t need any! I’ll be fine!!! No care needed for me!”

Of course, I definitely needed care and am grateful to have received it tenfold from my partner, roommates, and fellowship community.

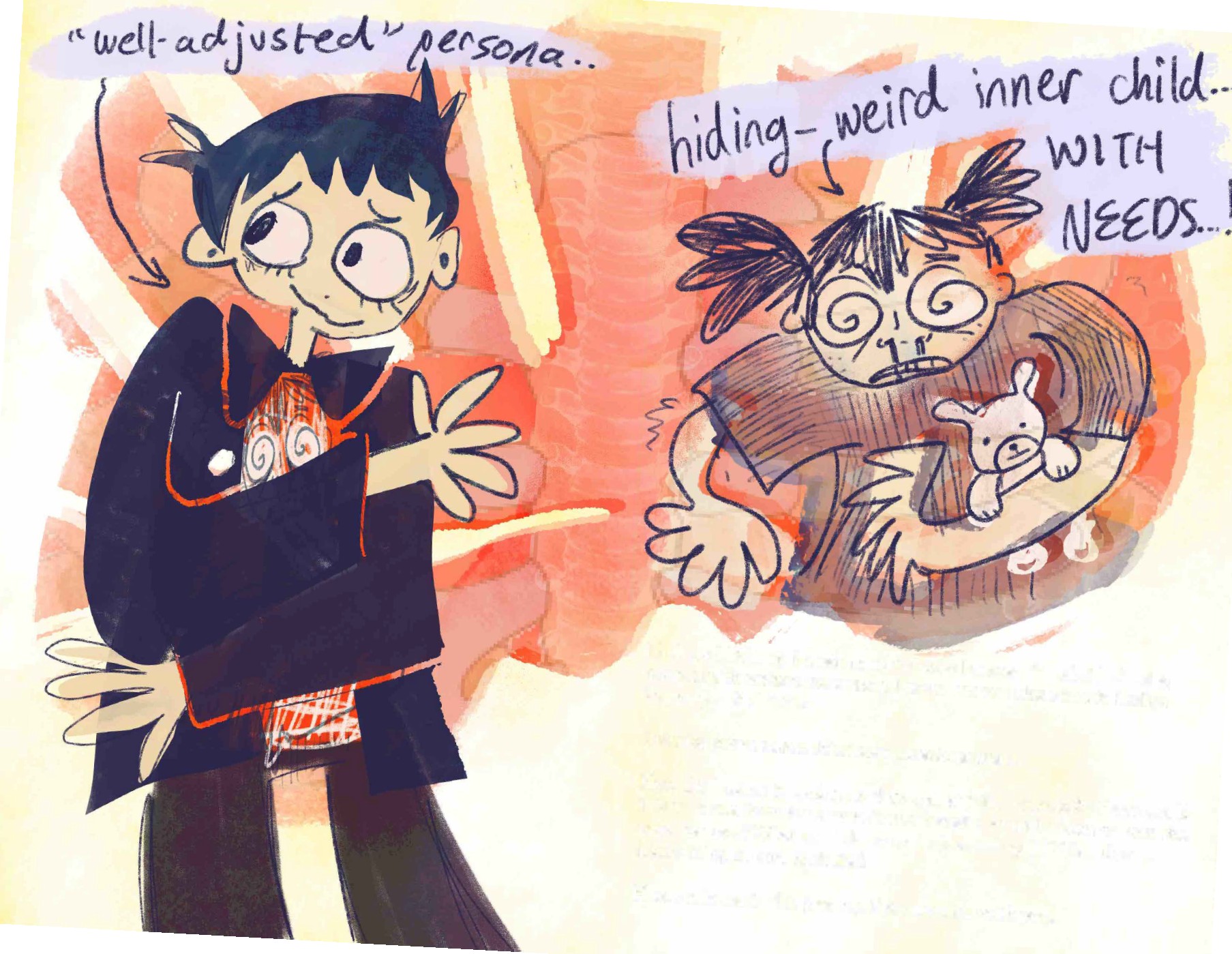

I never examined closely how I wanted that care to manifest. I really thought that swallowing my need for care was altruistic, a marker of being a good person, I don’t want to be a burden.

I don’t want to take too much time, or effort.

I’d like to be small. I’d like to be manageable.

I believe I hide my human need for care because I’m afraid of being open, and therefore vulnerable. I know I’m not alone in this feeling. Maybe you feel it too.

Thinking more about this, more questions arise.

How did I come to understand care as a finite resource? Where could it have come from for others? Who benefits when I refuse to own the need for care? What can I do to overcome this guilt? What does a future of open care look like?

Please join me in this journey, if it resonates with you.

Is care a finite source?

Let’s really define care here, because care is two things rolled into one. Care is both creating conditions of safety and nurturing said conditions. That second part- the nurture, the gentle attending and development, is collaborative and oft overlooked.

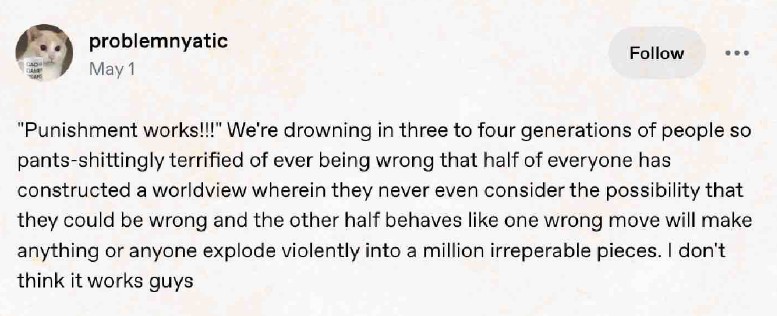

Like many folks, I grew up in an environment where care was not a nurturing act, but an obligation. Nurture was withheld if I was not a “good child.”

Reflecting on this point, this one tumblr post really feels resonant.

Likewise, care burnout is also a huge factor in how care feels finite. When a caregiver is not cared for in turn, the needed extension of self wears out the nurture required in care. This often turns up in caregiving as labour, and in nuclear family dynamics- mothers and eldest daughters. Reciprocity is a key in true nurturing care.

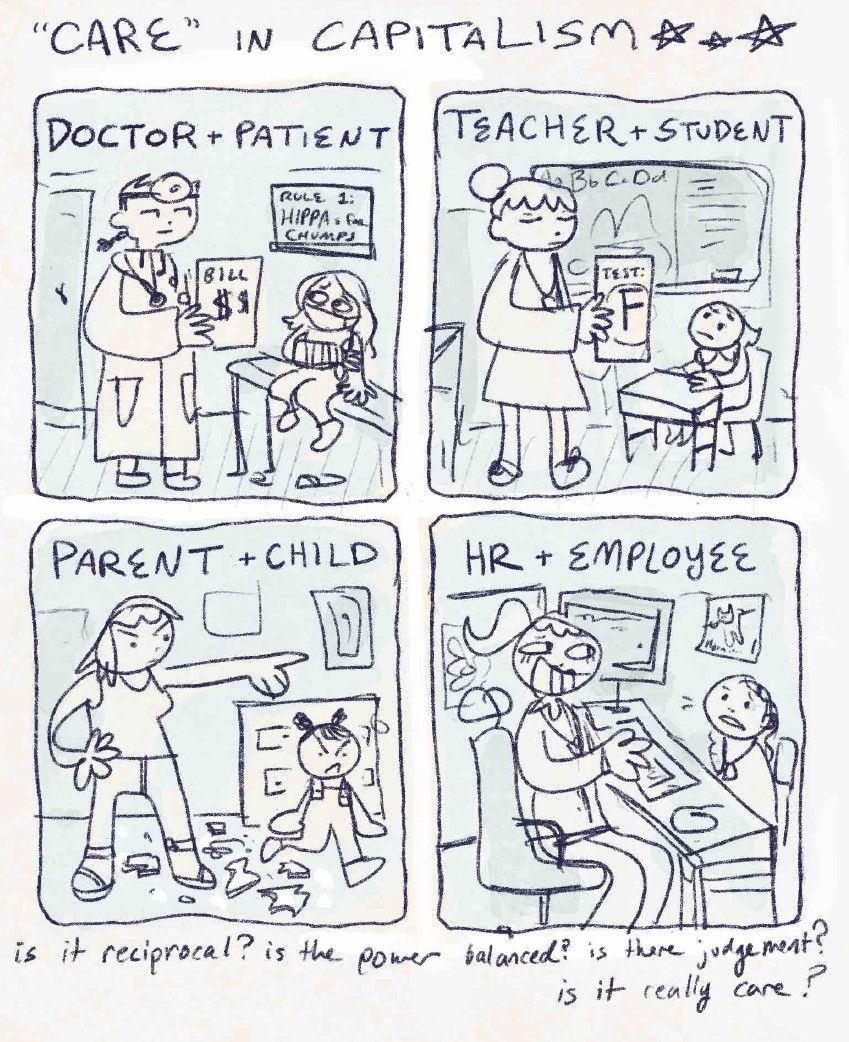

Imagine a world where care is collaborative- a doctor asks their patients what treatments work for them and care about their holistic health. Children’s autonomy is respected by their parents, and aren’t rigidly assessed by their educators. Work is done for people, and not for profits. Care in these senses are so much more sustainable!

Care isn’t meant to be a one way street. It does not need to be caregiver or caretaker as a rigid role. We are accustomed to this in our systems of capitalistic growth. Additionally, there is usually a power imbalance in care- the giver knows all, the receiver is lesser for needing this support.

Intersectionality

The way we approach care intersects with systemic privilege. Our systems are designed around one form of “normal” – and that norm is restrictive. To be anything but the norm is already seen as an adaptation that requires extra steps. To ask for basic needs feels like overstepping, asking to be comfortable is another hurdle. Marginalized folk often settle for bare minimum just to get by.

What if our systems of care were created with intersectionality in mind?

Merriam Webster describes intersectionality as “the cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect, especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups.” lntersectionality was first put into academia in 1989 by renowned critical race theory scholar Kimberle Crenshaw, and this theory guides how I process the different facets of grief and guilt in accessing care.

I have this guilt from systemic discrimination, and while this system is alive, I will carry it. However- I have the strength of my cultural practise and my community that shows me ways to care that are outside the system. That’s just the lived experience of one self only one grain of sand in the beach!

Imagine ways to care that respects the intersections of everyone’s lived experience, and how much more freeing it is! Instead of treating a need for care as an exception from the norm, we celebrated care as a crucial need for humanity.

People are tired. What if we weren’t? What if we were able to live in the abundance of community? What if instead of having to ask over and over, we molded our communities to be inclusive in care by default?

Removed from colonial input, care is meant to be spread across communities. One person is not solely responsible for the care of another, we are all responsible for the care of each other, and it happens in mutual exchange.

Care is not necessarily a finite resource. Care does not run out when we acknowledge reciprocity. Care grows in the harshest conditions, as care is how we survive. What is the use of a garden if only one person can reap the fruit?

Who benefits from the refusal to ask community for help?

It’s nice to feel self sufficient. Why burden anyone when I could effectively live on my “own?” But lets be real- nothing manmade in this world came about from just one person. From the clothes we wear, the food we eat, to the stories we enjoy, all of it is made by vast networks of people, collaborating, creating and working. Labour is made invisible thanks to layers and layers of societal dissonance.

Who would you be without the people who surround you? Without the small random acts of kindness, or without the culture that is built up and preserved by people you haven’t met? Who built the space you live in? Cleans the streets you walk? Individualism, the idea we can do it alone, is a myth.

Who benefits from this myth, anyways?

Of course it comes back to capitalism. It always does!

First of all, it’s so much easier to buy short term, immediate gratification than it is to work towards long term satisfaction. Capitalism counts on isolation and individualism to thrive, separating care from community is a great way to keep people from connecting on a deep level. Working towards long term satisfaction is HARD.

Secondly, built into the ethos of capitalism is the aspect of exponential growth. Capitalism is built on finite resource extraction extract more, and more, make that number, the profit, go up and up, with no regard to sustainability or humanity.

Care is the opposite of this. Care requires stillness, requires nurture, requires sustaining and nourishing what is already there instead of expanding it. When we stop to care for each other, capital suffers.

Remember the very beginning of quarantine? That momentary shutdown of capital, that thrust into isolation, and the odd seeds of care that grew from it? The brief moment of UBI through CERB and CESB was honestly what enabled me to move away from an abusive place, and allowed me to seek a community that supported me. Cynics say UBI can never work, but that glimmer of care in the fear of the still ongoing pandemic (wear a mask!) is what makes me think it could happen again.

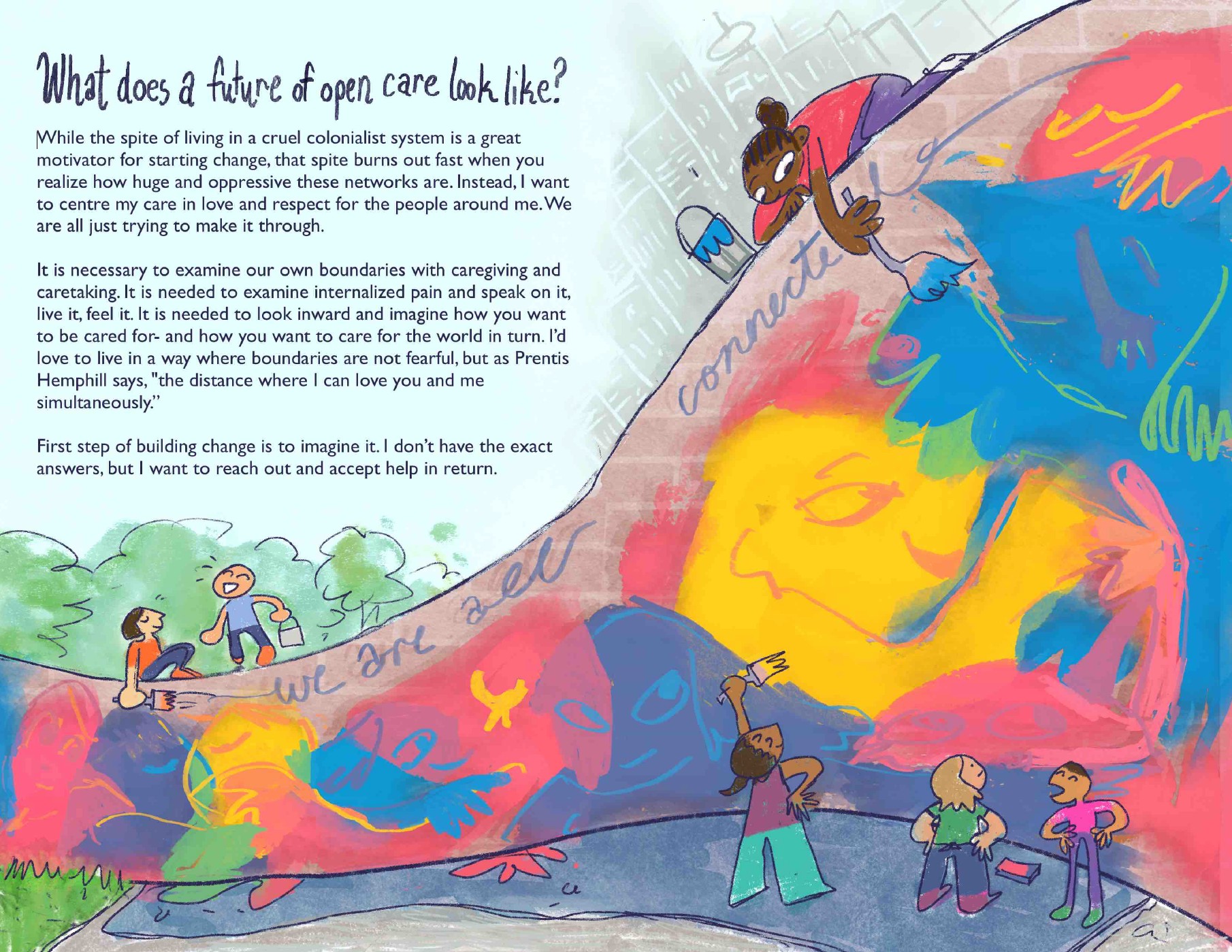

What does a future of open care look like?

While the spite of living in a cruel colonialist system is a great motivator for starting change, that spite burns out fast when you realize how huge and oppressive these networks are. Instead, I want to centre my care in love and respect for the people around me. We are all just trying to make it through.

It is necessary to examine our own boundaries with caregiving and caretaking. It is needed to examine internalized pain and speak on it, live it, feel it. It is needed to look inward and imagine how you want to be cared for- and how you want to care for the world in turn. I’d love to live in a way where boundaries are not fearful, but as Prentis Hemphill says, “the distance where I can love you and me simultaneously.”

First step of building change is to imagine it. I don’t have the exact answers, but I want to reach out and accept help in return.

References and further reading

The Care We Dream Of

edited by Zena Sharman

A collection of essays by queer folk centred around one question “how would it feel to look forward to seeking healthcare?” This book was lent to me by a friend and was the main guide into my questioning on guilt.

Kimberle Crenshaw on lntersectionality, More than Two Decades Later

Kimber/e Crenshaw for columbia.edu

An interview from Crenshaw that discusses intersectionality, the research, and how it is relevant in the modern rise of facism.

An Abolitionist’s Handbook: 12 Steps to Changing Yourself and the World

by Patrisse Cullors

An accessible read- honestly, abolition IO I. Discusses abolition in a way that highlights how you can take this framework into your day to day life.

The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House

by Audre Lorde

A short essay that illustrates how embracing our differences is how real change starts to shape Available. for free online at the Anarchist Library.

What It Takes to Heal: How Transforming Ourselves Can Change the World

by Prentis Hemphill

A trauma-informed guide that digs into care, healing, and forgiveness. Asks the question “What does it do to have healing at the center of every structure and everything we create?”

Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care

Mariame Kaba and Kelly Hayes

Reciprocity, to me, unlocks that barrier of care burnout. Kaba, Hayes, and a host of organizers ask the long term care question of “What fuels and sustains activism and organizing when it feels like our worlds are collapsing?”

About the creator

Kento (bat cities) is a Hāfu cartoonist and childen’s art educator based out of Hamilton, Ontario. He’s inspired by materials that kids can use, and illustrates stories based on togetherness.

© Kento Cady, 2025.

All texts and artwork are published with the permission of the artist. The creation and publication of this work was made possible with the support of Canada Council for the Arts, Government of Canada, Ontario Arts Council, and Government of Ontario.