Created by

Claudia Arana,

Fellow, I Love My Gig Ontario 2025

Published

February 4, 2026

Preface

Para Ellie taught me what it means to truly care.

Care as Resistance: Poems, Articles, and Practices is a work-in-progress. It brings together poems and essays alongside curatorial texts. Through this collection, the project seeks to highlight and explore diverse visions of care within artistic practices, emphasizing care as a form of resistance, healing, and critical engagement in contemporary art.

The conception of these reflections on care began during and after the pandemic, following a period of profound personal and professional exhaustion. As I delivered my first child while simultaneously curating and producing three art exhibitions for the City of Toronto’s Year of Public Art, I found myself caring for everyone—my newborn, my family, the artists, their work, and their communities, while neglecting my own needs.

The cumulative fatigue and emotional toll of navigating motherhood, caregiving, and cultural work during a global crisis prompted a deep and necessary inquiry into the true meaning of care: not as endless self-sacrifice, but as a radical, deliberate practice of balance, restoration, and boundary-making. These lived experiences became the seed for this project, reframing care not as a passive or secondary gesture, but as a site of resistance and political agency.

This work has been made possible through the support of ArtsPond’s I Love My Gig Ontario 2025 fellowship, whose care-centered, artist-led vision provided the time, space, and support to reflect, process, and bring these ideas into conversation through writing and artistic research.

The Revolution

The revolution whispers in small acts—

in the boiling of herbs passed down

by hands that remember the earth’s secrets,

in the slow circling of a comb

through tangled, unspoken grief.

It murmurs in the naming of pain,

when someone dares to say

« this hurt is real,

and it is not mine to carry alone. »

It lingers in the soil we turn

not only to grow food,

but to bury shame

and plant new beginnings.

Our resistance is not always loud—

it doesn’t always march or shout.

Sometimes, it brews in kitchens

where women hum lullabies

to the future they refuse to give up on.

It grows in compost,

where nothing is wasted—

even sorrow becomes fertilizer.

It grows in cradle,

where rest is offered like prayer,

where each breath is a balm

against a world that runs on exhaustion.

These gestures, soft and sacred,

reshape the world quietly—

like water wears down stone.

This too is revolution:

to nourish what capitalism depletes,

to mend what colonization fractures,

to choose presence

over performance,

and love

over labor.

Pedacito de tierra

This past year has been full of drastic changes, moments that have required both resilience and great flexibility. This experience has led me to reflect, as a migrant woman, on the notion of relaxation and self-worth in the lives of women, particularly those who migrate. I think about the silent and heavy burden that weighs on our bodies, compounded by the many other responsibilities faced by those who choose or are forced to migrate.

After my first conversation with artist Luisa Niño and Mariana Marin, Director of Legados, where we shared many of the challenges we have faced as immigrants, numerous questions arose. However, one in particular remained: When was the last time we truly experienced rest, relaxation, and peace?

I have met brave, productive, strong, kind, and often anxious women. Women who are creative, courageous, and compassionate, yet rarely appear truly relaxed or at ease. I have noticed how difficult it is for women to grant themselves unconditional permission to relax—without guilt, without apologies, without feeling the need to earn it.

This reflection highlights a yearning to embody a state of relaxation: a woman who values rest, pleasure, and self-compassion without guilt or excuses. It articulates a vision of an intuitive woman who lives according to her values and prioritizes her well-being over productivity and external achievements.

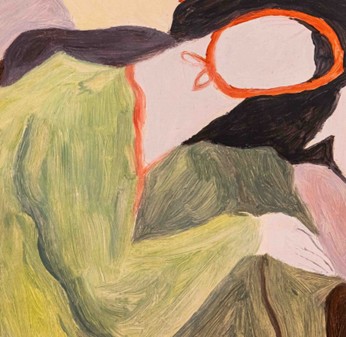

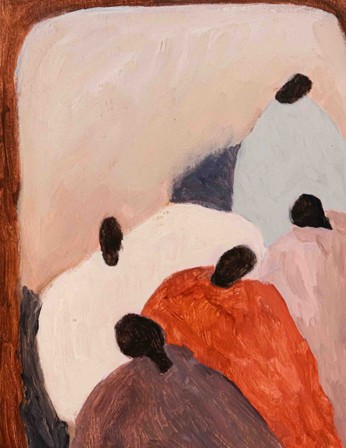

During her residency in the summer of 2024, Luisa was invited to delve into a state of slowness and gentle practices aimed at reshaping responses to stress, the constant pressure to produce, and the relentless need to do. At the same time, she reflected on self-worth, rest, and intrinsic pleasure. This, of course, intertwines with the continuous exploration of her cultural Mexican heritage and her journey as a migrant woman.

The works presented in Pedacito de Tierra are the result of moments of deep meditation, reflection, and a slowed pace that allowed the artist to create without pressure or oppression. These pieces capture the long hours of a warm summer that Luisa spent in Legados’ studio. A temporary studio that became her creative safe space. There, amidst reading poetry and her thoughts, Luisa allowed ideas to flow freely, exploring themes of care, rest, and relaxation in organic ways.

Pedacito de Tierra invites us to slow down, and to breathe with calm. It proposes reevaluating the burdens we carry—not just physical ones, but emotional and mental—and questioning their weight and validity in our lives. This call to reflection emphasizes the importance of prioritizing well-being, understanding that rest, calm, and self-compassion are necessary and subversive acts and to install a space of resistance and self-affirmation, as an opportunity to reconsider our priorities, and ultimately, to value well-being and pleasure as fundamental and intrinsic rights of our existence.

La Malinche

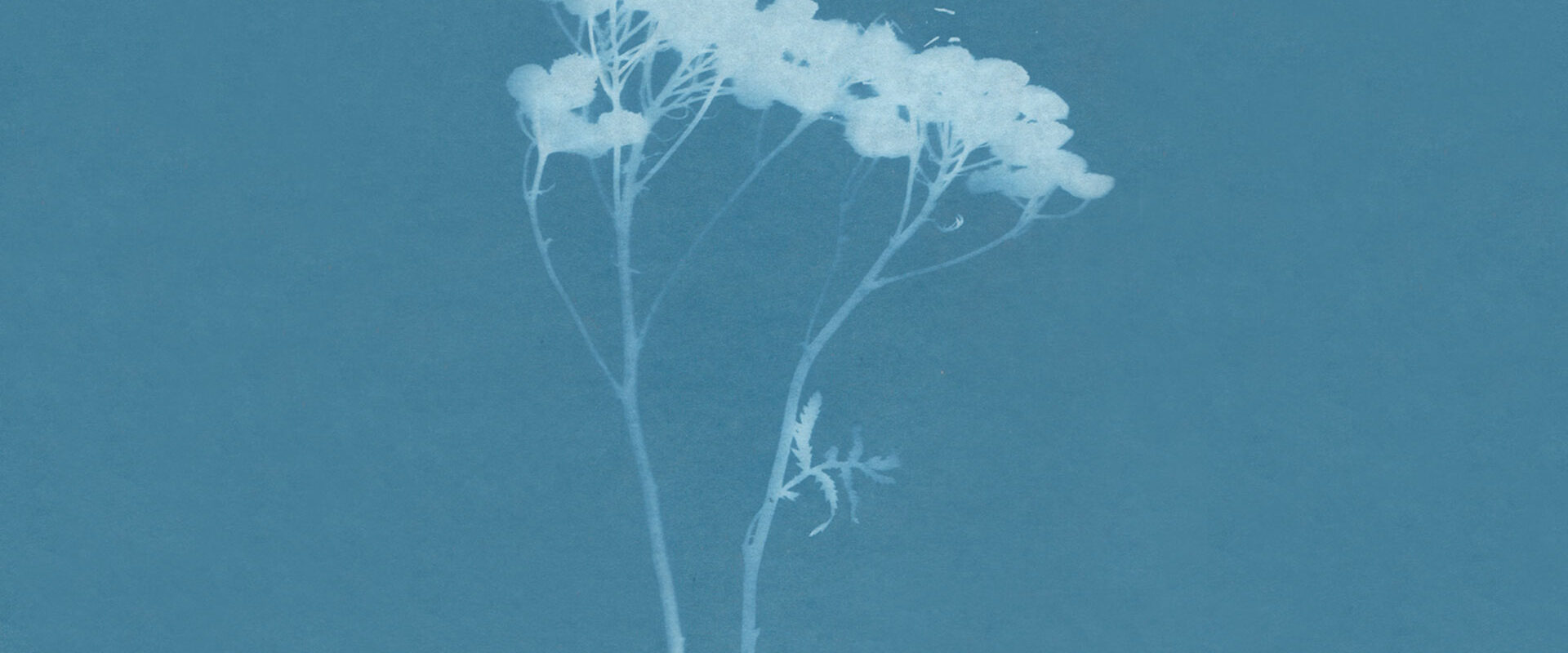

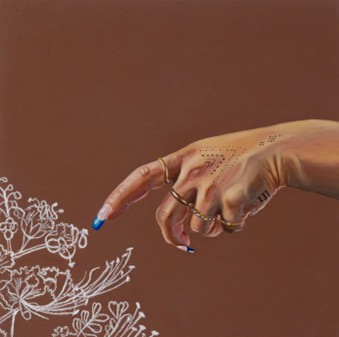

Michelle Peraza, a Cuban–Costa Rican Canadian artist based in Toronto, develops a material- and research-driven practice that investigates colonial histories, botanical symbolism, identity, and resilience. Among her works is the 2023 series, Peacock Flower, La Malinche, Malintzin, flos pavonis, Caesalpinia pulcherrima, Red Bird of Paradise, which centers on the peacock flower (Caesalpinia pulcherrima), also known as La Malinche (Peraaza 2023).

The peacock flower carries deep historical and cultural significance. Its name, La Malinche, references La Malinalli, a Nahua woman who was sold into slavery as a child and later given to the Spanish upon their arrival in what is now Mexico. As Hernán Cortés’s interpreter and cultural mediator, her story has come to embody complex colonial narratives of mediation, betrayal, and submission— layers of meaning that echo within the very name of the plant (Karttunen 1997). However, Peraza’s engagement with this symbol transcends conventional historical readings, reclaiming La Malinche as a .

Through oral family histories and botanical investigation, Peraza is interested in how Caesalpinia pulcherrima was traditionally used among Indigenous and Afro-descendant women as an abortifacient and for other medicinal purposes. This intimate knowledge of self-managed reproductive care was systematically excluded as the plant entered European botanical archives during colonial expansion. While the plant was celebrated in European gardens for its aesthetic beauty, its deeper meaning—linked to women’s bodily autonomy—was deliberately silenced. This erasure reflects what scholar Londa Schiebinger describes as « agnotology », or the colonial production of ignorance, particularly regarding reproductive knowledge (Schiebinger 2004).

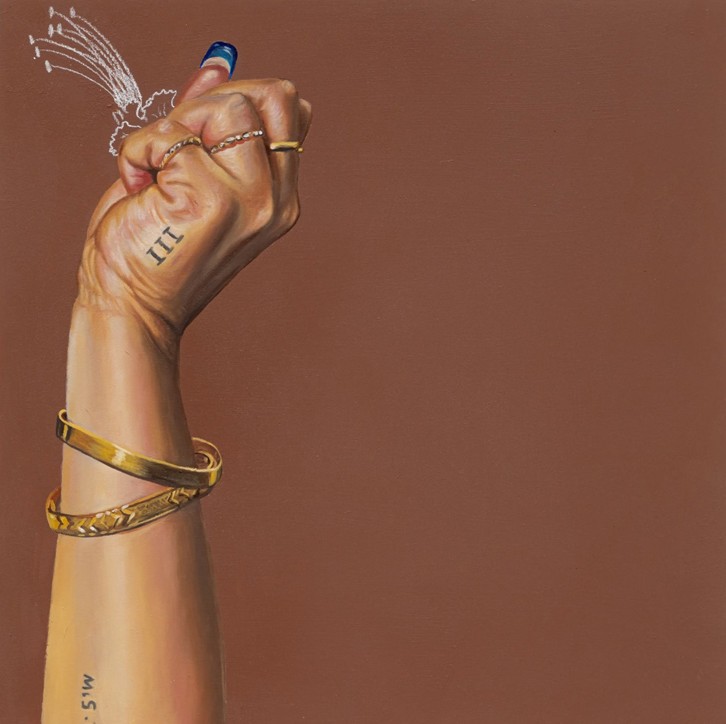

Peraza’s work becomes a feminist act of reclamation and an intimate gesture of care. By linking the botanical figure of La Malinche with the historical figure of Malintzin, she challenges patriarchal narratives that have traditionally framed Indigenous women as traitors or passive subjects of conquest. Instead, she highlights their roles as knowledge-bearers, healers, and agents of sovereignty over their own bodies. Through her layered material practice—combining acrylic, gesso, charcoal, and intricate botanical forms—Peraza not only claims visual space but reclaims historical agency, centering reproductive care and embodied wisdom.

This act of care extends beyond historical recovery, offering visibility and continuity to knowledge systems that persist despite centuries of colonial suppression. By emphasizing the peacock flower’s role in reproductive care, Peraza exposes how ancestral knowledge empowered women to exercise control over fertility, even when such knowledge was stigmatized or criminalized. This artistic intervention transforms private, often hidden realms of reproductive decision-making into public acts of remembrance and self-determination.

Here, her work resonates strongly with Gloria Anzaldúa’s concept of spiritual activism, which merges personal healing with collective resistance. Anzaldúa writes: « The work of mestiza consciousness is to heal the split that originates in the very foundation of our lives, our culture, our languages, our thoughts » (Anzaldúa 2009). For Anzaldúa, healing, care, and self-reclamation are not merely personal acts but radical interventions that challenge systems of domination. This notion of healing as resistance echoes powerfully in Peraza’s practice.

Furthermore, Peraza’s work also aligns with the decolonial critique of Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, who addresses the long-standing silencing of Indigenous and subaltern knowledges under what she terms « internal colonialism. » Cusicanqui argues that decolonial work must not simply resist colonial narratives but recuperate submerged epistemologies, bodily practices, and worldviews that colonial power has long sought to suppress (Cusicanqui 2018). Peraza’s work participates in this recuperation by rescuing women’s knowledge of the peacock flower as part of a broader struggle for reproductive sovereignty.

In Peacock Flower, La Malinche, Malintzin, flos pavonis, Caesalpinia pulcherrima, Red Bird of Paradise, Michelle Peraza re-envisions the historical entanglements of colonialism, patriarchy, and reproductive rights. She brings forward botanical knowledges erased through colonial violence, confronts gendered oppression, and asserts the continuing relevance of reproductive self-determination—anchored in healing, remembrance, and care. In doing so, Peraza’s work exemplifies care as an act of radical resistance: an embodied, feminist, and decolonial practice of reclamation.

The Garden

There is a garden I carry inside,

roots curling in quiet, unseen lines.

No one sees the weight of the rain,

how each drop feeds what remains.

The world rushes on

but I stay low, my fingers in the land.

Turning the soil where old wounds fell,

planting what I could never tell.

Care is not loud, care is not fast,

it is seeds beneath the past.

In broken ground, I plant the light,

tending softness through the night.

The garden grows where no one sees —

this quiet labor sets me free.

I’ve carried others, their branches, their weight,

forgot my own roots in their ache.

But now I kneel where silence sings,

and let the earth unbind my wings.

— la flor resiste sin anunciar su resistencia.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my deep gratitude to artists Luisa Niño and Michelle Peraza for their generosity, openness, and trust in allowing me to engage deeply with their artistic practices. Their willingness to share their work, processes, and reflections opened meaningful spaces for dialogue, critical inquiry , and expanded understandings of care within artistic practice. Thank you also to ArtsPond, whose vision of care-centered, artist-led research provided not only time and resources but also a nurturing framework for contemplation, creation, and community building. I am deeply thankful for their commitment to fostering spaces where care is not only a subject of inquiry, but also an integral part of the creative process itself.

Claudia Arana, 2025

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, G. (2009). The Gloria Anzaldúa reader (A. L. Keating, Ed.). Duke University Press.

Karttunen, F. (1997). Rethinking Malinche. University of Texas Press.

Niño, L. (2024). Pedacito de Tierra [Artwork]. Montreal: Summer Residency at Legados Legados – Institut latino‑américain de transmission de la langue et de la culture.

Peraza, M. (2023). Peacock Flower, La Malinche, Malintzin, flos pavonis, Caesalpinia pulcherrima, Red Bird of Paradise [Painting]. Toronto.

Rivera Cusicanqui, S. (2018). Un mundo ch’ixi es posible: Ensayos desde un presente en crisis. Tinta Limón Ediciones.

Schiebinger, L. (2004). Plants and empire: Colonial bioprospecting in the Atlantic world. Harvard University Press.

© Claudia Arana, 2025.

All artworks, images, and texts are published with the permission of the artist. The creation and publication of this work was made possible with the support of Canada Council for the Arts, Government of Canada, Ontario Arts Council, and Government of Ontario.